You may want to skip down to the actual book review section if you’re only interested in my thoughts on The Silmarillion. I say this because the first part of this last review of 2024 will linger on personal anecdotes and experiences that may or may not interest you.

I don’t want to bore you with the struggles of my early childhood, but it is probably enough to say that things were not always great at home. I developed a taste for escape early. I found Dungeons and Dragons and then Lord of the Rings some time between ages 10 and 12. I checked Fellowship of the Ring out of the Lehi school library many times, but it was too much for me and it took until I was 12 for it to stick. I spent countless hours flipping back and forth between the tiny map of Middle Earth published in a small paperback edition, and the passages in the book, trying to meticulously follow the path of the Fellowship. I remember being very frustrated that I couldn’t find Isengard on the map, despite its central role in the books only to figure out some time later that the tower had a second, Rohirrim-assigned name of Orthanc, and that’s what was on the map.

My slow, patient, plodding approach to understanding Lord of the Rings eventually ingrained a sense that this story had a realness to it. Here were “real places” with vast histories stretching back into an imagined antiquity. Languages felt real. Tolkien’s seemingly endless descriptions of trees and the English comfiness of a Hobbit hole, and the taste of fresh strawberries prompted my very young mind to draw on what it knew and thankfully, what it knew was England. My mother had been ensuring that we traveled back to her homeland for many years. And so, an inescapable alchemic blending of “real” and “fantasy” fermented in my mind. Middle Earth was England, England was Middle Earth. Hobbit holes were akin to 30 Queens Road, Felixstowe (My grandparent’s home).

The Flights from Arizona to England begin at night and end with the sun cresting over the horizon. When the plane dips below the inescapable cloud cover, I tear up every time as the brilliant patchwork of varying shades of green explode into view and I hear Gandalf say, “The grey rain-curtain of this world rolls back, and all turns to silver glass. And then you see it. A far green country, under a swift sunrise.”

When we traveled to England to bury my grandfather, in a quiet moment of reflection my brother Ian said, “Nothing bad ever happened here” and I think that sums it up the best. England was where we went physically to see true nature, pretend to be knights in real castles, experience real adventure, and become exposed to the vast sweep of history as told to us by our loving grandfather, grandmother, aunts and uncles. Middle Earth is where I went mentally, to stay connected to that place. I hope that helps explain, in part, why I love these books so much. They are the closest thing to scripture for me (a bold and perhaps blasphemous claim, even for Tolkien) but it’s truly how I feel. I feel connected to my family, my home, and that far green country via these works of towering imagination.

The Book

The Silmarillion isn’t for everyone. It is Tolkien’s creation mythology blended with (mostly) the history of the First Age of Middle Earth. It is divided into three parts

· The Quenta Silmarillion – The History of the Silmarils (which is primarily a history of the creation of the world and of the First Age.)

· The Akallabêth – The story of the downfall of Númenor

· Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age – Which is a summary of the history just prior to the War of the Ring.

The Quenta Silmarillion -

The Quenta Silmarillion is the lengthiest part of a relatively small book, but don’t let the page count fool you, it is a demanding read. My previous somewhat blasphemous reference to this book as scripture was intentional. This is probably the third time I’ve read the book, but it was only at 51 years old that I realized Tolkien wrote this as scripture. The language is the language of mythology. Just as the Hobbit is written for younger audiences, and The Lord of the Rings is written for an adult audience, Tolkien’s very intentional writing style for The Silmarillion is evocative of both mythological writing and scripture. Tolkien uses formal and archaic language, including sentence structures and vocabulary reminiscent of the King James Bible or other ancient texts. He creates a sense of grandeur and timelessness, placing the events in a distant, mythic past.

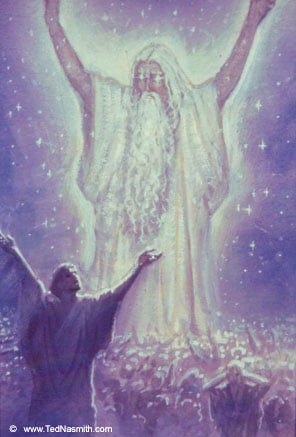

In Tolkien’s mythology Eru Ilúvatar (God) is the supreme being of Eä (all creation). He creates the Ainur (Demigods) who “sing” Arda (the world) into existence. Some of the Ainur chose to become part of Arda and descend onto it becoming the Valar, who live in Valinor (heaven) and who wish to enact the will of Eru Ilúvatar, except for one, Melkor, who sings a song of discord putting himself in conflict with the will of Ilúvatar. He is, essentially, Lucifer.

The first born of Ilúvatar (Elves) awake in Middle Earth and are guided back to Valinor by one of the Valar. Here, the son of Finwë, Fëanor forges the Silmarils, brilliant jewels that contain the light of Ilúvatar. These jewels are eventually stollen by Melkor who flees Valinor into Middle Earth. Some of the Elves of Middle Earth pursue him there, to wrest back the Silmarils from his grasp. The story of The Quenta Silmarillion is the story of the various elvish houses and kings in the First Age and their war on Melkor (renamed Morgoth) to re-capture the Silmarils. Beleriand, the land mass of Middle Earth in which these tales take place, is eventually buried beneath the sea when the Valar, Elves, and faithful men bind Melkor and thrust him through the Doors of Night, into the void in the culmination of the War of Wrath.

That summary doesn’t remotely do justice to the depth and grandeur of the work. Tolkien writes stories of tragic heroes (Of Túrin Turambar), poetic stories of love and sacrifice (Of Beren and Lúthien), stories of bravery against impossible odds (Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin), and stories of betrayal and tragedy (Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin). He blends his deep knowledge of real-world mythologies, Christian sensibilities, and linguistic expertise into a breathtaking fictional history that can’t help but feel real.

Here are some bits of Trivia that I loved;

· In Lord of the Rings, Galadriel’s power prevents the enemy from spying on, or even crossing into her realm of Lothlórien. In the Silmarillion we learn that when Galadirel left Valinor for Middle Earth, she dwelt with King Thingol and Melian in Doriath. Melian was an immortal Maia (think angel) who created the Girdle of Melian around Doriath, protecting it from Melkor. The inference is that Galadriel learned this ability from Melian, who was her friend.

· Lúthien was the daughter of Thingol and Melian. She was both Mia and Elf. She was described in the text as “the most beautiful of all the children of Ilúvatar to ever live.” She gave up her immortality to marry a mortal man whom she loved and sacrificed for Beren to accomplish his life’s task. I was overwhelmed when I learned that Tolkien is buried with his wife in Oxford, under a gravestone that labels her as his Luthien, and him as Beren.

· This one isn’t “fact” but I came to understand that Gandalf’s sword, Glamdring, was originally wielded by the King of Gondolin, Turgon. When Melkor finally discovered the location of Gondolin he sent orcs, warewolves, balrogs and dragons to destroy the hidden city. Of course, after Melkor was defeated some of his servants escaped. One of them, Durin’s Bane, was the Balrog that Gandalf fought in Moria. I like to think that the Balrog of Moria participated in the destruction of Gondolin, and recognized the sword of Turgon, coming to exact justice, in Gandalf’s hand.

This post has already gone on far too long so I will try to quickly summarize the last two parts of the book.

The Akallabêth -

Due to their valor and fealty to righteous Elven kings in the war against Melkor, one particular tribe of men, the Dúnedain were granted a kingdom. The Valar themselves raised an island out of the sea and placed it midway between Middle Earth and Valinor, and they named it Númenor. Over time the Dúnedain spit into two factions, the King’s Men, and the Faithful. The King’s Men began to rankle at the strictures of the Valar which forbade the Númenoreans from sailing to the Undying Lands. The Faithful wanted to keep their oath. Eventually the King’s Men become so proud that they sail to Middle Earth, conquer Sauron, and bring him back in chains to Númenor. Sauron though, secretly allowed for all of this to happen and he uses the opportunity to further foment discord in the hearts of men. Eventually, a vast armada of ships sails in open war against Valinor and the Valar are so incensed that they break the world, causing it to become round and lifting Valinor into the heavens. The faithful were able to flee in time and eventually found the realms of Arnor and Gondor in middle earth.

Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age –

This very short portion of the book tells the history of Sauron’s machinations to create Rings of Power and use them to control the free peoples of Middle Earth. It tells of the eventual downfall of Sauron at the Battle of Dagorlad and how his spirit fled into the east, later to return and take up residence in Dol Gudur in Mirkwood. Eventually the White Council comprised of Saruman, Gandalf, Galadriel, Elrond, Cirdan, and others chased Sauron from his fortress, but it was too late to defeat him. He fled to an already established Barad-dûr and began to gather strength for what would become the War of the Ring.

A Final Note

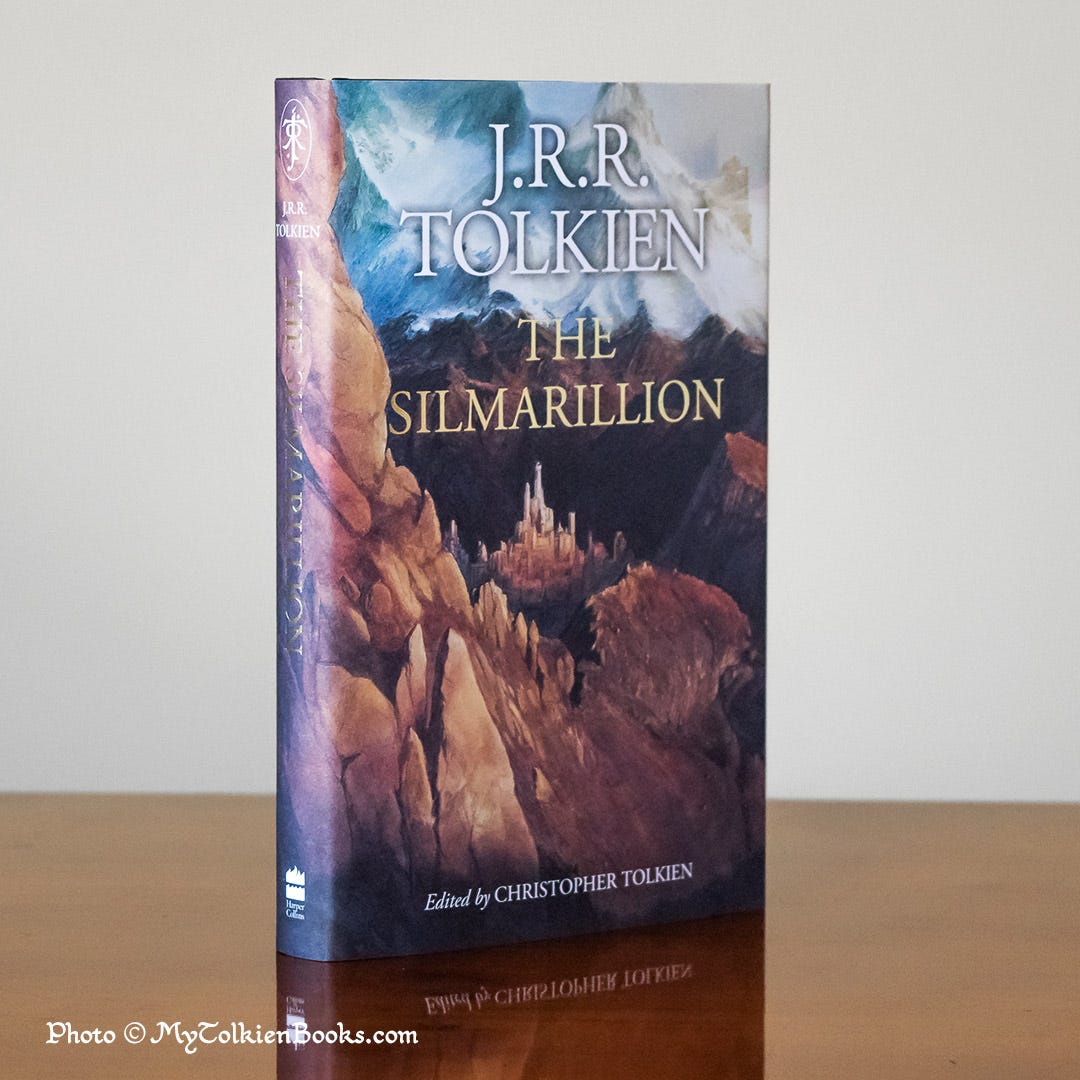

Obviously I would recommend this book. How could I say otherwise. It’s stories and themes touched me deeply, and I got to re-experience sitting in my room, reading a complex story while referencing maps and entries on the internet (thank you all the good folks at tolkiengateway.net and lotr.fandom.com). Tolkien once said (paraphrased) that he created Middle Earth in order to produce a situation in which he could hear his languages spoken. Because of this I did something that I highly recommend you do. I bought both the hardbound book to read, but also purchased The Silmarillion as read by Andy Serkis. It was a real treat to hear Tolkien’s words spoken by Serkis with the correct pronunciations. Serkis provided distinct voices for many of the characters and “performed” many of the scenes. This only elevated the experience.

Thanks for reading this far, if you made it. On to 2025!

It is not the Valar who sink Numenor and make the world round. They don't have the authority nor in terms of the later the power to do so. Tolkien's mythos is monotheistic. Only Eru can perform these acts. Manwe temporarily relinquishing his governance of the world and calls upon the one to take over when this happens....

Great review! I really loved the personal context. I read "The Silmarillion" when I was in junior high and not ready for it. This review made me want to pick it up again. And it made me want to go to Oxford to visit Tolkien's grave. Such a great photo!