What Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Is, and Isn't

I was asked over on my YouTube channel to explain what Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT) is. I had mentioned that it was drilled into me in graduate school that I should select a theoretical point of view and then practice from it. For the uninitiated, a theoretical viewpoint is a set of underlying assumptions, concepts, and principles that effectively erect a framework from which one analyzes and conceptualizes. In psychology there are many different frameworks. Psychoanalysts view phenomena quite differently than Behaviorists, or Cognitive Behaviorists.

To understand Cognitive Behavioral Theory, it’s important to understand what came before it, mostly to understand what it is not. Most folks unfortunately see therapy through the lens of psychoanalysis, primarily because that’s what’s leaked into pop-culture over the years. I’ll try to lay out a brief history of the various movements within psychology leading up to CBT. The truth is, I am not a historian and despite having more than a passing familiarity with this history, I am probably going to get some facts wrong. The intent here though is not to give you a true history of psychology, but rather to understand what CBT is.

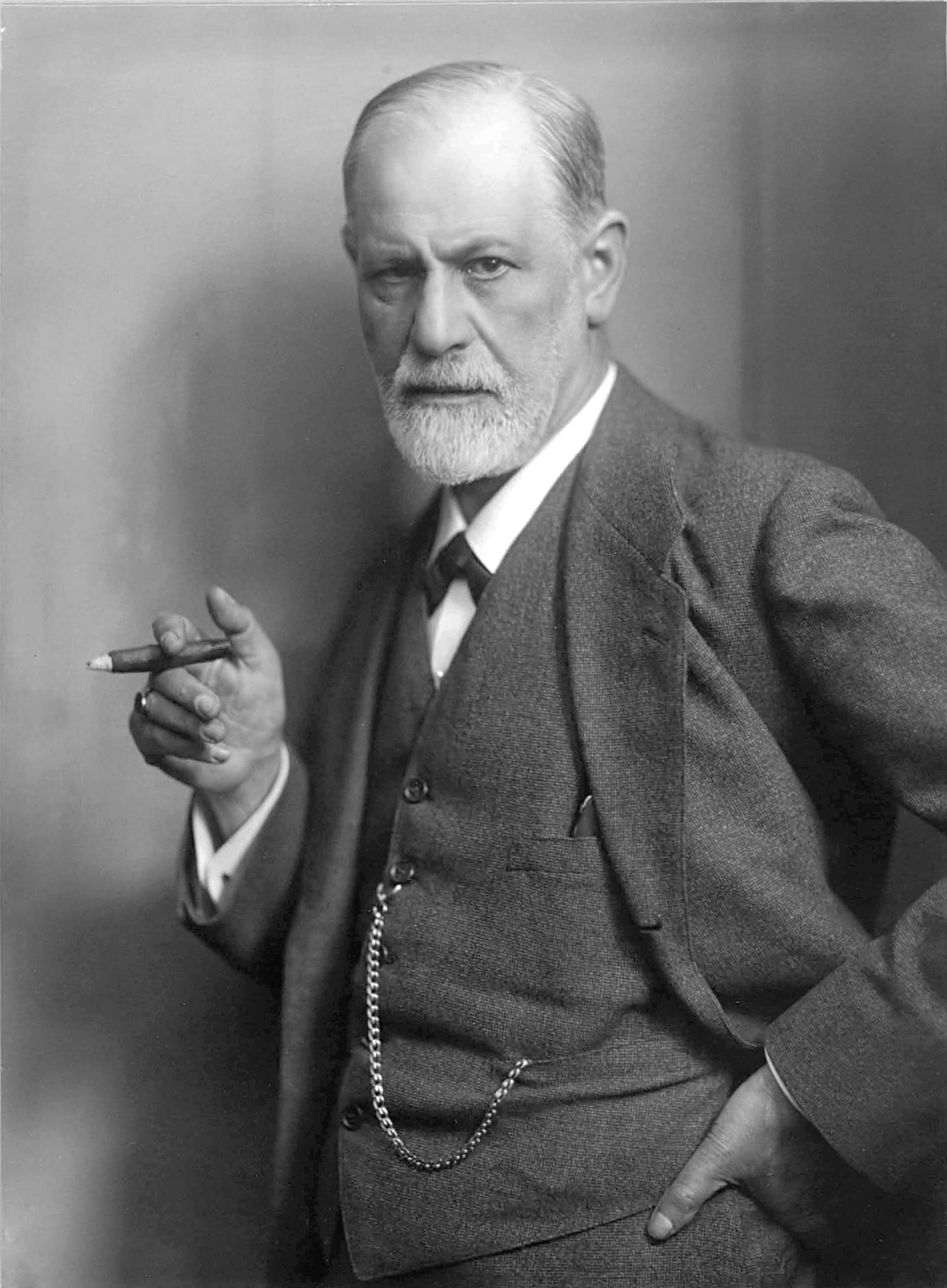

Most people believe that psychology began with Sigmund Freud, and while that is not the case, for our purposes he is a good place to start. Psychoanalysis, Frued’s theoretical framework, rests on four key concepts:

The Unconscious Mind: Freud believed that the larger part of the human mind was something called the unconscious. Through a process known as repression, unwanted and distressing thoughts were pushed down into the unconscious. Psychiatric issues arise when these unwanted thoughts begin to escape containment of the subconscious.

Defense Mechanisms: Defense mechanisms serve as shields, protecting us against internal conflicts and anxiety. Whether through repression, denial, or projection, our ego employs these strategies to manage distressing thoughts and emotions, shielding our conscious selves from their impact.

Stages of Psychosexual Development: Human development occurs across a series of psychosexual stages, each marked by a focus on different erogenous zones and the conflicts they provoke. From the oral stage, where the infant's needs center around the mouth, to the genital stage marking puberty and beyond, successful navigation of these stages is crucial for healthy psychological growth. Each stage presents its unique challenges, and demands resolution for progression.

Structure of the Psyche: Freud dissects the human psyche into three interconnected entities—the id, ego, and superego—each wielding its influence over our thoughts and behaviors. The id, driven by the pleasure principle, seeks immediate gratification of primal urges. In contrast, the ego, guided by the reality principle, acts as a mediator between the id's demands and external constraints, navigating the complexities of reality. Finally, the superego represents the internalized moral compass, striving for perfection and adherence to societal norms.

Using these to guide his conceptualization of his patients, Frued’s therapy focused primarily on helping clients exhume these problematic thoughts, memories, or desires from their subconscious. Psychoanalytic theory’s core assumption is that if patients could release these from their subconscious, depressions and anxieties would come under control.

There were, however, several theoretical and practical problems with Psychoanalytic Theory. The practical problem was that patients didn’t really seem to get better, even after years of therapy. Success was quite sparing, and progress slow. But the deeper problems for Psychoanalytic Theory were that it was too subjective and lacked empirical evidence. It wasn’t falsifiable. How can one test for the existence of a subconscious? How can one predict or measure an Oedipus complex? Critics of Psychoanalytic Theory stated it was overly complex, failed at predicting behavior, and wasn’t very good at achieving its stated aims.

Behaviorism

Those criticisms formed the basis of a new psychological theory called Behaviorism. Behaviorists, in reaction to the “looseness” of Frued’s theory, focused exclusively on the belief that observable behavior is the primary focus of study, and that internal mental processes should be disregarded.

Behaviorists believed that all behavior, including complex human behaviors, can be explained in terms of simple stimulus-response associations. This focus on simplicity of stimulus-response coupled with a rejection of anything that was not observable led to two key concepts of behaviorism:

Classical conditioning, popularized by Ivan Pavlov showed that one could train an organism to respond in a particular way to a stimulus. Ring a bell when you provide a dog with food, and he will salivate at the food. Eventually, if you do this enough, the dog will salivate when you ring the bell alone.

Operant conditioning associated with B.F. Skinner one trains an organism to respond by adding or removing stimulus (positive and negative reinforcement) or punishment (think mouse, cheese, maze).

While this theory was much more successful at predicting some behavior it still had some significant problems. It was criticized for completely ignoring human mental processes. Yes, the mind is ineffable, but one cannot hope to ignore it and produce a coherent theory of the mind. Behaviorism was better at prediction than Psychoanalysis was, but it could only predict behavior in simpler organisms (rats, dogs, etc.). While its focus on observable facts coupled with its scientific approach designing experiments and testing hypotheses were helpful in moving psychology further, it was criticized for being overly reductive.

Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT)

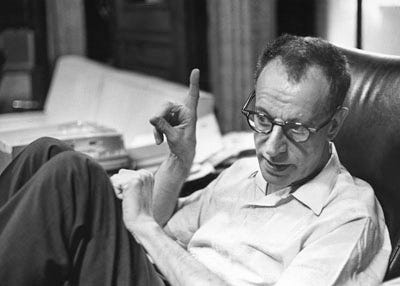

While Behaviorism was developed in response to Psychoanalysis and the lack of scientific rigor therein, it’s important to understand that CBT was not a similar reaction to Behaviorism. In fact, it was itself, also a reaction to Psychoanalysis. What we call CBT today was developed initially by Albert Ellis who then called it Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy. Ellis was disenchanted with psychoanalysis, specifically with how long it took, how expensive it was for his patients, and how infrequently they got better. He disliked Psychoanalysis’s focus on past events, and he was looking for a theoretical framework focused on the present and future. Ellis, having struggled with anxiety and depression himself, had found relief in a study of ancient Stoicism, a philosophy which rested on the idea that the source of most human suffering lay in irrational thought patterns.

Aaron Beck was a psychiatrist who, separately from Ellis, was also dissatisfied with psychoanalytic theory and its poor success rate at treating patients. It was Beck who noted that depressive patients tended to share similar patterns of negative thinking, cognitive distortions, and maladaptive patterns of behavior. It was Beck that recognized that one might adapt the scientific approach of Behaviorism while integrating cognition back into the study of psychology.

So, what is it?

Where Behaviorists believed that there was only stimulus and response, this belief broke down when applied to humans. Let’s say you and I dear reader are transported to an amusement park where they are celebrating the grand opening of their newest, fastest, scariest roller coaster. We are both standing in front of it, and we are both attempting to figure out, independently, if we want to ride it.

If the stimulus is the roller coaster, then what is the predictable response? Obviously, there is none. Most clients, when presented with this question correctly observe that different people behave differently in the same situation. You may feel excited and decide to ride on the rollercoaster, while I may feel anxious and even afraid, and decide to sit this one out. So, if one cannot predict how people will behave when prompted with the same stimuli can we at least explain what prompts the different outcome?

Here, CBT states that between stimulus and response rests the world of cognition (thought). You might have fond memories of riding roller coasters in the past, and your mind projects a positive and exciting expectation on the idea of riding one again. You experience excitement because of your thoughts and eagerly get in line. Conversely, I may have memories of a poor experience, or maybe I have no memories at all, but I simply imagine myself flying off the roller coaster and plummeting to my death on the concrete below. I experience anxiety because of these thoughts and my emotions and thoughts motivate me to avoid this fear by sitting out the ride.

How does it work?

Cognitive Restructuring:

Therapists help clients develop skills that will allow them to identify their own thoughts. Most people don’t realize how habitual their thought process is, and most of the time the thoughts they have rest outside of their awareness. By learning how to observe what one is thinking, clients can get a handle on what is generating their unpleasant symptoms.

Once clients understand what it is they are thinking, then typically the therapist teaches the client how to dispute those thoughts. Most thoughts that generate depressive or anxious symptoms are irrational. I want to be careful here as people typically have a negative reaction to the word irrational. Being sad and in mourning, for example, that a loved one or family member has passed away, is NOT irrational. To conclude that because of their passing life is no longer worth living is. Clients learn how to dispute irrational thoughts and test to see if they experience a reduction in symptoms.

Behavioral Activation: Behavior and cognition are interrelated. This means, that while cognitive restructuring focuses on cognition, behavioral activation focuses on encouraging clients to do things that once brought pleasure or meaning to their lives, even when they don’t feel like doing it. Often the therapist will pose this as a behavior experiment: You believe that going for a walk or exercising in any capacity isn’t going to help your mood improve? How about you rate your mood prior to exercise, then go do it, and rate it again. See if it helps.

Exposure Therapy: In cases of anxiety or phobias, exposure therapy is used to gradually expose individuals to feared or avoided situations. Over time, repeated exposure reduces anxiety and desensitizes individuals to their triggers.

Skills Training: CBT often includes teaching specific coping skills, problem-solving strategies, and relaxation techniques. These skills empower individuals to manage stress effectively and cope with challenging situations.

CBT is one of the most well researched and well supported therapeutic modalities. If you’re considering therapy feel free to ask your therapist from what theoretical orientation they practice and feel free to ask them any questions that you might have relative to CBT.